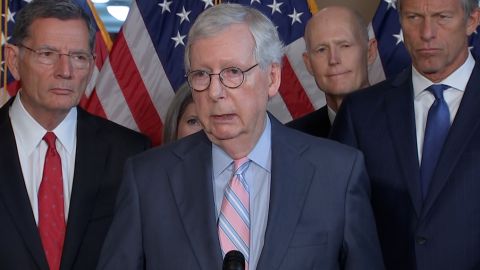

Opinion: Mitch McConnell is making Senate history

Editor’s Note: Scott Jennings, a CNN senior contributor and Republican campaign adviser, was a former special assistant to President George W. Bush and a former campaign adviser to Sen. Mitch McConnell. He is a partner at RunSwitch Public Relations in Louisville, Kentucky. Follow him on Twitter @ScottJenningsKY. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

CNN —

On Tuesday, Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky becomes the longest-serving party leader in Senate history, passing the late Mike Mansfield of Montana, who was Democratic leader from 1961 to 1977.

McConnell’s most recent term atop the Senate GOP conference was won on a 37-10 vote, a continued display of political dominance quite unusual these days in Washington.

I’ve known, worked for and most recently observed McConnell as a political analyst for over 25 years. His ability to maintain his leadership position in a party that has undergone such turbulent change is fascinating. Many politicians have come and gone during his tenure, while others have spun like weather vanes in a futile attempt to keep up.

But the stoic and understated McConnell changes little, which serves as a source of frustration for his enemies, not to mention for more than a few of his fellow Republicans and the reporters assigned to cover our democracy.

I’ve often heard McConnell remark that when he took office in January 1985, he would peer over his desk from a dark corner of the Senate and think, “None of these people are ever going to die, quit or get beat.” He wondered often if his tenure would be one of longevity and consequence, or a short-lived trip on the backbench.

Indeed, McConnell has become one of the most consequential political figures in American history. His longevity and deal-making abilities draw comparisons to his idol, Henry Clay, a fellow Kentuckian who served as US senator, House speaker and secretary of state.

Unlike Clay, however, McConnell never pined for the presidency. Rather, he set out to master the greatest deliberative body in the world. From the back row, McConnell moved up, building a reputation as a campaign street fighter and savvy operator. He won two hard-fought reelections in 1990 and 1996 (Kentucky was still a blue state back then) and then worked his way up to become Republican leader in January 2007 following stints as the Senate GOP’s campaign chief and conference whip.

McConnell’s initial and most recent elections as party leader both came during moments of turmoil for the GOP. He ascended the top spot 16 years ago after Republicans took a “thumping” in the 2006 midterms, as then-President George W. Bush put it.

And in 2022, Republicans failed to regain the majority as Senate Democrats rode former President Donald Trump’s bizarro coattails to pick up one seat, relegating avid football fan McConnell to another term as, in the GOP leader’s words, “defensive coordinator.”

McConnell has never had it easy. Of his 16 years as Republican leader, two came under a lame-duck Bush, four under an erratic Trump and the rest under Democratic Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden. He never had more than 54 Republicans (and as few as 40) during his tenure, while the previous record-holder Mansfield never had fewer than 54 Democrats and usually had well over 60, the Senate’s magic number to establish complete political power.

What McConnell has accomplished, he’s done so with thin margins and often from a politically weak position. He achieves gains for his party where he can (the most recent omnibus spending bill scored massive increases in defense spending, for instance) but never lets his partisanship or ideology outweigh his governing responsibilities.

His operating protocol is to achieve the most conservative legislative outcome within the given circumstances, a strategy that has smashed headlong into the strident revolutionaries in his party who prefer no outcomes beyond scoring the next cable TV booking.

McConnell elicits hatred from his political opponents because they rarely can get the best of him. Many Kentucky Democrats hated him first, having failed to oust him seven times.

A number of the political press came next. In my experience observing McConnell, his efforts to stop campaign finance reform and his unwillingness to freewheel with journalists in congressional hallways seemed to put off some reporters.

Washington Democrats are not to be outdone. Their resentment of McConnell securing three Supreme Court seats during Trump’s tenure serves as an eternal flame of rage to light their party’s way, not to mention their frustrations at his use of Senate rules to thwart parts of their agenda.

For many Democrats, McConnell’s holding Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat open in 2016 but filling Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat in 2020, despite both Supreme Court vacancies occurring during presidential campaigns, is particularly infuriating. McConnell drew a distinction between whether government was divided at the time (it was in 2016 but not in 2020); Democrats, of course, did not. Either way, these were among the most consequential decisions of McConnell’s career.

Lately, the populist right has come for McConnell, accusing him of not wanting to win the 2022 midterms. McConnell-affiliated groups were on track shortly before the election to raise and spend more than $380 million. Trump, in comparison, spent around $20 million from his personal war chest despite having plenty more in the bank and a large hand in determining the GOP’s general election roster. This criticism must make for a hilarious joke in the Democratic cloakroom.

Trump is put out with McConnell for not going along with the former President’s election denialism, issuing hateful statements about him and launching a racist tirade against his wife, Elaine Chao, who was transportation secretary in Trump’s Cabinet.

McConnell refuses to respond, clearly because he understands the adage about the futility of wrestling pigs in the mud — and perhaps because he takes some pleasure in ignoring such a self-absorbed narcissist.

Depending on whom you ask, McConnell is either too conservative, too liberal, too partisan or not partisan enough. The sands of politics have washed in and out with the tide since McConnell became leader, but only our perspective has changed. McConnell hasn’t moved much at all. He’s not a showman, and he’s not much bothered by media criticism. To some, that makes him ill-suited for politics during this performative age.

But to this observer, it seems that our democracy needs at least a few sturdy trees whose roots run deeper than the latest ideological fad or conspiracy theory.

It was inevitable that an institution and an institutionalist such as McConnell would eventually become the object of scorn for the burn-it-all-down populists who wield increasing influence in American politics. A recent polling analysis published in The Washington Post found that, since 2018, “Republicans lost confidence in every institution that we asked about except one: the local police. …”

But McConnell believes deeply in two things: the role of strong institutions in our society, and that America, civilly and militarily, is a force for good in the world.

While Trump and his offshoots thrive on weak institutions and the utopian promises of isolationism, America, historically, has not. Their view is that the US cannot be strong at home if it pursues policies that make it strong abroad.

“On this mistaken view, courage and compassion are polar opposites,” McConnell said in a December speech to the US Global Leadership Coalition. “They see strength and sympathy as opposite ends of a spectrum. In this perspective, hard power and soft power are rivals, and prioritizing our interests is mutually exclusive with prioritizing our values.

“But here’s the good news: The entirety of American history tells us that is completely and totally wrong.”

This unfolding battle in the Republican Party will perhaps define the final chapter of McConnell’s long career as GOP leader. Will Trump return? Will the GOP succumb to isolationism and a wrongheaded view that America can only walk or chew gum, but certainly not both at the same time?

While this debate rages over the course of an upcoming presidential primary, McConnell will surely have no intention of changing or going anywhere. He’s got four years left on his current Senate term, and he has seemed to me in recent conversations as engaged and determined as ever to press his worldview forward.

His battle with Sen. Rick Scott of Florida over the GOP conference leadership position was invigorating to McConnell, and his recent public statements show an intention to restore a winning attitude to a party that hasn’t won much at all lately.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/02/opinions/mitch-mcconnell-senate-leader-milestone-jennings/index.html