Tony Vargas in Nebraska: One man’s Covid crusade in rural America

In Nebraska, which has some of the worst racial disparities when it comes to Covid-19 cases in the country, the state’s sole Latino lawmaker tried to strengthen protections for meatpacking workers, all while confronting his own personal tragedy. It was a battle against time that revealed much about race, politics and workers’ rights in the pandemic.

On the afternoon of 29 July, in the main chamber of Nebraska’s shining state capitol building, in the midst of one of the strangest legislative sessions in state history, a young senator stepped to a microphone.

Tony Vargas was dressed in a trim blue suit, dark hair neatly parted to one side, a pair of trendy thick frame glasses perched on his nose over a green cloth face mask. The 35-year-old lawmaker stood out amongst his mostly greyer colleagues, but also because, along with two black and one Native American member of the legislature, he was one of only a few people of colour in the chamber. He is the state’s only Latino senator.

“I would like to thank you all in advance for hearing me out on this,” he began.

Vargas – a first term Democrat in a Republican state, representing a diverse urban district that straddles downtown and South Omaha – was about to make a big ask of his colleagues, and hoped he could rely on the Nebraska legislature’s reputation (perceived or real) for being more collegial than others. It is the nation’s only unicameral, nonpartisan legislature, with just a single body of 49 senators.

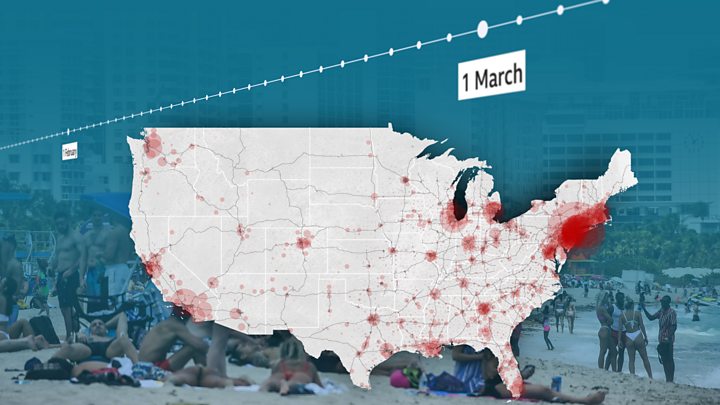

Like many state governments, the Nebraska legislature abruptly shut down in March in order to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Now, after four months, the senators agreed to reconvene to finish the session in 16 days over the course of four weeks.

Image copyright

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Many lawmakers continued to shake hands, others refused to wear masks, despite the fact that one of their own, Senator Mike Moser, had only recently recovered from a serious case of the virus. Nebraska is one of a handful of states that never had a shelter-in-place order nor a mask mandate.

Nevertheless, Vargas was attempting to persuade his colleagues to allow him to introduce a new bill to enact protections from Covid-19 in the meatpacking industry, an issue he’d been working on for months. It was an action which required special permission to “suspend” the rules of the senate – a Hail Mary in a legislative session that had only 10 days left in it. But after weeks of other attempts, he had run out of options.

“Over the last several months I’ve been working closely with workers at meatpacking plants across the state,” he said. “What is happening in these plants – not only how workers are being treated, safety and health measures that need significant follow-through, and misinformation spread that everything is fine – is what brought us here today. Is what brought me here today.”

He led with the data. Of the state’s 25,000 Covid-19 cases, one in five of them was a meatpacking worker. Of those, 221 workers were hospitalised and 21 of them died. According to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, Nebraska ranks second in the nation in Covid-19 related deaths among meatpacking workers.

On top of that, 60% of the state’s confirmed cases were in Hispanics, while they make up just 11% of the overall population. (Since August that percentage has dropped to 40%, but it may still be the worst racial disparity for Hispanics for Covid cases in the country.)

The vast majority of Nebraska’s meatpacking workers fall in this demographic, and the state’s biggest hotspots flared in counties that contained factories. Many of the rest of the workers are immigrants and refugees from countries like Ethiopia, Somalia, Myanmar and Bhutan. For months, Vargas’ office had been receiving distraught emails, calls and Facebook messages from workers and their family members, pleading for more oversight.

Currently, safety measures in plants recommended by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration are classified as “guidance”, and though dozens of meatpacking plants have experienced outbreaks, inspectors have issued only three modest fines related to Covid.

“I am asking you to help me to try to fully understand what’s happening in these meatpacking plants,” Vargas continued. “If you don’t see the urgency and why this situation demands all of us to act now, then I am at a loss.”

The vote that day was merely to allow introduction of the bill. The bill itself, if passed, would require the state to enforce Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines in the plants such as social distancing, free and readily available PPE such as masks, and require that management inform workers in writing if someone they came into contact with tested positive, among other measures.

For a full hour, the senators argued. A few spoke in support of the motion. Others fretted that new regulations would throw sand in the gears of the nation’s food supply chain. Still others denied that there was a problem at all, or blamed the workers’ living conditions for the spread.

“Twenty-one deaths – but when was the last one?” one senator asked. “This issue has already been addressed.”

When Vargas took the microphone back just before the motion went to a vote, there was an extra edge in his voice.

“I am pleading with you,” he said. “We can save more lives.”

A dull bell clanged to signal the start of the vote, and a board listing each senators’ surname lit up in green and red lights.

The final tally: 28 yays and 10 nays. Eleven senators declined to vote.

“The threshold was 30 to suspend the rules,” the senate president said from the dais. “The rules are not suspended.”

Later that evening, in his basement office in the capitol, Vargas was in a dismal mood. It wasn’t easy, one of his legislative aides explained, to feel like the “de facto advocate for all Latino residents in the state”.

What really stung was that Vargas had done something in service of the motion that, up until that point, he’d tried to avoid – he’d spoken to his colleagues about his father.

In March, the coronavirus swept through the Vargas family, sickening his 71-year-old mother, his oldest brother and his 22-year-old nephew. And then, on 29 April, Vargas’ father Virgilio – an otherwise healthy 72-year-old who still worked full-time as a machinist – died of Covid-19.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

His senator son had hoped that hearing some of the harrowing details of the 29-day battle with the virus might persuade his colleagues to prioritise meatpacking workers’ health above business concerns. But he was wrong.

“When I share that with my colleagues, and it just rolls off some of their backs, like, ‘Well, that doesn’t impact me, so we’re not going to allow you to do this’ – it pains me,” he said. “It took everything out of me when I’m thinking that I’m the only one in this body that actually lost somebody to this virus.”

Only nine days of the session remained.

Vargas remembers the first phone call like this.

It was early April. The caller was a young woman, just out of college. Both her father and her uncle worked at a meatpacking plant in rural Nebraska, where rumours were spreading that there were positive Covid cases among the employees.

“I don’t know what to do,” he recalled her saying. “I’m trying to convince them not to work. I’m trying to convince them to take it seriously.”

Her father and uncle both needed the money. They were essential workers – but it seemed too dangerous. What should she do?

“I didn’t have an answer for her,” Vargas said.

Just a few weeks earlier, he had the same conversation with his parents – his 71-year-old mother Lidia was continuing to go to work at a bank, his 72-year-old father Virgilio continued on as a machinist. Both could have retired long ago – after immigrating as a teenage newlyweds to New York City from Peru in the 1970s, his father spent over 50 years working all sorts of jobs to keep his young family afloat, on factory assembly lines, as a courier, a handyman, as a sidewalk peanut vendor.

They could have retired at any time, but the couple decided “just one more year”.

Image copyright

Antonio Vargas

Virgilio Vargas and family

On the same day that the Nebraska legislature announced it would be shutting down, Lidia Vargas told her son she wasn’t feeling well. By Saturday, when Virgilio tried to go into his shop, he found he couldn’t breathe properly.

“I just had this terrible feeling in my gut,” Vargas recalled.

At the same time, Vargas was working to head off the virus’ spread in Nebraska. It had always been clear to worker and immigrant rights organisations around the state that meatpacking plant employees were uniquely vulnerable in the pandemic.

The plants are enormous, with thousands of workers entering and leaving the plants at the same time, sharing locker rooms and cafeterias, and standing less than a foot apart on the production line. Because they needed their pay cheque, they were unlikely to walk away from these jobs even if conditions were dangerous, and because many did not speak English as a first language, they wouldn’t know how to advocate for themselves.

On 25 March, a coalition of organisations including Vargas penned a letter directly to meat packing plants, appealing for social distancing, additional sanitising measures and more generous leave policies for at-risk workers.

“Together, we can limit the spread of this virus while we keep the food supply chain safe and consistent!” it read.

Vargas said he heard nothing back.

On the same day that the letter went out, across the country in Long Island, Lidia and Virgilio Vargas sat in line at a drive-through Covid testing site. Three days later, they found out they were both positive for Covid-19.

Vargas spent the weekend calling his parents every three hours, jotting their symptoms down in a notebook. When he heard his father’s increasingly booming cough and shallow breathing, he made an appointment for a chest X-ray.

On the way home from the appointment, Virgilio swerved off the road. He was having so much trouble breathing he couldn’t drive. Vargas’ mother picked him up and brought him back to the hospital. Early the next morning, while Vargas was on the phone with the attending physician, his father went into cardiac arrest. Twenty agonising minutes later, the doctor called back to say that Virgilio had stabilised, but was on a ventilator – where he would remain for 29 days.

On 9 April, Vargas and his wife Lauren sat in front of a laptop and recorded a Facebook message for his constituents.

“About two weeks ago after showing symptoms of coronavirus, both of my parents tested positive. Less than two days later, my dad’s symptoms got much worse and he was admitted into the hospital,” Vargas said into the camera. “My dad is really struggling and he’s fighting this virus and we’re hoping he will get better soon.

“I’m hoping that hearing from somebody that you know may bring some urgency to the situation that we’re all dealing with now,” he continued. “I don’t want any other families to go through this.

If there’s anything my family, I or my office can do to help you during this time, please don’t hesitate to reach out.”

Not long after he posted the video to Facebook, he was contacted by the first daughter of a plant worker. She was far from the last.

“Every time it was a son or daughter, or niece or nephew, of an older father or mother or uncle or aunt that’s working in the plant. They’re like younger kids, either high school to my age, that feel helpless and don’t know what to do,” he said. “All of them were Latino.”

Not long after came the outbreaks.

A Tyson plant in Dakota City reported a total of 786 cases. A Smithfield plant in Crete racked up 330 cases related to either workers or their close contacts. In Grand Island, 260 positive cases were recorded among the workforce at JBS Beef Plant. According to reporting from the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, Nebraska leads the nation in Covid cases among meatpacking plant workers.

Read more stories by Jessica Lussenhop

While fielding calls from distraught factory employees, and strategising with a coalition of workers and immigrants’ rights organisations on what to do next, Vargas was constantly on the phone to doctors at his father’s hospital.

It was Vargas who had to approve the doctors to make small incisions in his father’s lungs to try to relieve some of the pressure. It was Vargas who would get the good news in the morning that his father’s CO2 levels had improved and then by night find out things had got worse again.

He arranged Zoom calls between his mother and brothers, and the nurses who would hold the phone up to their father’s emaciated face, hoping that behind all the wires and tubes he could hear them.

On 13 April, Vargas’ oldest brother Gene – the son closest to their father – woke and found that he could barely move. His temperature was 103.4 degrees and he was soon diagnosed with Covid as well.

On 18 April, the first meatpacking plant worker in Nebraska died.

A few days later, Vargas got the call from his father’s doctors.

“They said they’d never seen anybody with carbon dioxide in their lungs and their blood this high,” he recalled. “They said, ‘We think that this might be the end for him.'”

They offered Vargas and his family a rare opportunity. At a time when most Covid patients were dying alone, the hospital was allowing some exceptions. If the Vargas’ wanted to come say goodbye, they would allow it.

At the height of the pandemic in New York and against his mother’s wishes, Vargas boarded a plane.

“I knew that there are so many people that did not get to say goodbye,” he said. That included Gene, the favourite son, who because of his symptoms was not allowed in.

For two nights, in a negative pressure room, wearing an N95 mask, a face shield, two gowns and a heavy plastic smock, Vargas sat, holding his mother’s rosary in his father’s hand.

- Coronavirus: ‘We’re still waiting at home for them to come back’

At 4:17am, 29 April, Virgilio Antonio Vargas – a 72-year-old machinist, shop steward, the man his family called “Silverfox”, the tough-love dad, the penny pincher, who loved soccer and the Jets and telenovelas but also terrible American sitcoms like Two Broke Girls, who was just learning how to enjoy the fruits of his labour, who just two months earlier was cliff diving in Peru – died alone after his exhausted son had gone home for the night.

When Vargas remembers his father now, just three short months after his death, his mind goes back to election night in 2016.

Growing up, the Vargas family did not talk politics. They talked about work, and work was something you did with your hands.

When his youngest son announced to his family that he was running for the Nebraska state senate at 31 years old, with no prior experience in public office aside from three years on the Omaha school board, his father gave him a blunt assessment.

“‘You’re not gonna win because the people that win are usually white. They’re usually rich or wealthy or have influence,'” Vargas recalled. “He said it with love, but he said it to me.”

Image copyright

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

He tried to convince his father that this was different – his district was almost half Latino, many living below the poverty line, yet had never had a senator who looked like them. He could talk to them about healthcare access, job access, school improvement and housing equality – and he could do it in Spanish.

When the weekend before election night came, Virgilio and Lidia flew to Omaha and spent 12 hour days canvassing for their son. One night, Virgilio went so long and so hard that his phone died, he got lost and had to be rescued. His sons were shocked by his enthusiasm.

“My dad wasn’t that kind of person,” remembered Gene Vargas. “We were all taken aback by that.”

Vargas remembers his father on election night- a contest that saw the Latino vote in the 7th district increase by two-and-a-half times. Virgilio stood in the front row of the victory party, holding hands with his mother and pumping his fist in the air.

“For the first time really ever, my father believed that what I was doing, and that the position I was in, actually can help move the needle and help people,” Vargas recalled.

The memory of his father’s late-life political awakening both inspired and haunted Vargas, particularly as he struggled to figure out a way to help the meatpacking workers. In the weeks immediately following his death he arranged Zoom calls between senators and meatpacking workers to try to build support in the legislature for new regulations.

In June, he penned a letter to Republican Governor Pete Ricketts, imploring him to “define and mandate a policy to protect Nebraskans working in meatpacking and poultry plants across the state”, hoping a campaign of public pressure might inspire action. It was signed by 23 fellow senators, five of whom were Republicans.

Instead, the governor announced that meatpacking plants no longer had to publicly disclose their positive case numbers (his office did not respond to multiple messages seeking comment).

So Vargas started work on a bill he knew was almost certain to fail. He didn’t feel he had a choice.

“That’s what I told my dad I was going to do. That’s why he believed in it. He didn’t believe it was a bunch of bullshit,” he said. “If I don’t do it, who is going to do it?”

On a punishingly hot day in Lincoln, a young man in a black baseball cap and face mask sat outside the Nebraska state capitol in a socially distanced line that stretched all the way inside, snaking through the hallways to Hearing Room 1525. He held in his arms a large, ornate framed photograph of a smiling, bearded man in a suit coat, to whom he bore a striking resemblance.

Christian Muñoz had taken the day off of work and driven two-and-a-half hours from his home in South Sioux City, Nebraska, to testify before state lawmakers about his father, Rogelio Calderon Munoz, who died of Covid-19 at 53 years old.

Both father and son had worked side by side at the Tyson meat processing plant in Dakota County, Nebraska, which saw one of the worst Covid-19 spikes per capita in the state. Both father and son contracted the virus. While 23-year-old Muñoz stayed asymptomatic, his father rapidly declined just days after telling his son he was feeling weak.

Muñoz tried to go back to work at Tyson, where he deboned huge slabs of beef at a rate of 50 seconds per carcass. But then he passed his father’s former post and saw someone else standing there. He never went back.

Some of his friends warned him not to go to Lincoln. They said it might affect his current job, that he might even get sued by his powerful ex-employer.

But Munoz had already made up his mind.

“He wasn’t just a worker at a plant, you know?” he said. “He deserves justice. It deserves to be recognized. That’s why I’m here.”

Christian Muñoz with girlfriend Kenia Ramirez and Christian Jr

Although Muñoz had never met Vargas, they shared remarkably similar, terrible experiences.

Like Vargas’ father, the elder Munoz spent weeks on a ventilator. Like Vargas, Christian Muñoz made the difficult medical decisions on behalf of his father and his family. Like Vargas, Muñoz had talked cheerfully to his grey-faced father through a Zoom call, hoping his voice would do some good.

Like Vargas, Muñoz was allowed the rare opportunity to sit at the bedside after doctors told him there was nothing more to be done.

“I played his favourite songs,” he said. “It just was very sad. He looked like he was just suffering at that point.”

While Muñoz waited in the beating sun outside with dozens of others, Senator Vargas was inside introducing the hearing.

The fact that it was happening at all was a small miracle. When the motion to introduce his new bill failed the week prior, Vargas pulled a new manoeuvre – he added the same language in the bill as an amendment to an existing bill that had nothing to do with meatpacking workers. Then he went to the chair of the committee the bill was in and pleaded for a hearing.

According to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, 39,000 meatpacking plant workers across 40 US states have contracted the virus and 185 have died. Of the top 50 hotspots in the US, most are prisons and jails, but the rest – save for the naval ship the USS Theodore Roosevelt – are meatpacking plants. Worker safety in the plants became a cause championed by former presidential candidate and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker. But to date, no public hearings of any kind had occurred on the subject.

Vargas’ would be the first.

“I’m really hoping you take this to heart and it also changes what you believe is possible,” Vargas told the seven-member committee in his opening. “We’re the only body who can do something about this.”

And then, one by one, for the next four hours, the speakers came.

The committee heard – at times through a translator – about how, while conditions had improved in some of the plants since the spring, implementation of safety precautions was inconsistent from plant to plant. They heard about how workers’ masks – once soaked with animal blood and sweat – were not replaced. How the conveyor belts proceeded at their usual speeds even when three or four people were gone, leading employees to work at frantic and dangerous rates.

A plant worker and union steward told them that when federal inspectors from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration had come to her job at a JBS plant, management took them to a carefully cleaned section of the factory instead of showing them the real conditions on the line.

(In response, a spokeswoman for JBS wrote that “OSHA investigators direct the tour of the facility”. OSHA confirmed there are four open inspections at the JBS Beef Plant in Grand Island which they have six months to complete, and said no further information is available until that time. “The Department is committed to protecting America’s workers during the pandemic, and OSHA has been working around the clock to that end,” the spokeswoman wrote.)

A representative of the East African Development Center of Nebraska said that his members, many of whom are Somali, were so scared to miss work while sick that they were taking Ibuprofen in the morning to bring down their temperatures.

Eric Reeder, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 293, wearily ticked off a list of stories he’d heard from his members – everything from workers being written up for asking about positive cases to bathroom breaks being denied on understaffed lines – before he sighed and tossed his notes aside.

“The truth of the matter is that the employers are telling you that they’re giving out plenty of masks and they are giving them masks, but they’re not replacing them as needed. The distancing is nonexistent on the lines,” he said. “The employers, as long as they’re not mandated to do something, aren’t going to do it.”

A former meatpacking worker named Gabriela Pedroza told the committee that while she was thankful and proud of her old job, her friends and family still working in the plants were suffering.

“It has gone from smiling and laughing when we see each other to tears of fear – fear of getting sick, missing work and fear of speaking up to request safety,” she said, her voice quavering.

In all, 34 people spoke in favour of the amendment. No one representing the meat industry came, instead mailing in their letters of opposition.

When the BBC asked about the safety concerns raised at the hearing, representatives from JBS and Tyson responded that workers are provided as many masks as needed throughout the day.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

“They are not punished for asking questions related to COVID-19, they are allowed to take bathroom breaks and line speeds have been reduced due to our social distancing efforts,” wrote a spokeswoman for JBS.

“We’ve implemented social distancing measures, such as installing workstation dividers, providing more breakroom space, erecting outdoor tents for additional space for breaks where possible, and staggered start times to avoid large gatherings as team members enter the facility,” the Tyson representative wrote, adding that there are “very few active cases” in Dakota City.

“The cost of… COVID-19 related measures has been enormous, totaling over $500 million to date,” wrote a spokesman for Smithfield. “Our level of active cases among our domestic employees remains a fraction of one percent. These figures clearly demonstrate the robustness of our COVID-19 response. The numbers don’t lie.”

None of the three companies provided an up-to-date coronavirus case count for their Nebraska facilities.

When Muñoz entered the hearing room carrying his father’s portrait, the committee chair told him props were not allowed.

“I’ll just set it right here,” he said, placing the frame upright in a chair, facing the committee.

There was a lot Muñoz wanted to say. He wanted the committee to know that his father had been a talented singer, that he’d been in the middle of recording a new album. He wanted them to know that he was so beloved by the music community in South Sioux City that they’d posthumously given him first place in a talent show. He wanted them to know how excited his father had been when Muñoz told him his girlfriend was pregnant, how they’d sat together after work talking about baby names.

He wanted them to know that his father had died without ever meeting his grandson, Christian Gael, who was born five days later.

But he only had five minutes.

Instead he told them that his father was a US citizen, that he lived alone and so it was doubtful he contracted the virus elsewhere. He told them about the delays in getting PPE and how when they asked their supervisors about the virus, they were laughed off or told the contagion started at a Somali housing complex. He told them how his father continued going to work, even though he was scared.

“I’m here to honour my father because the company never did,” he said into the microphone. “Our family never received any condolences, even though earlier in April we were repeatedly told to be proud because we were feeding America… There are times when I think my father would still be alive if proper precautions were taken early on.”

He paused slightly.

“My father’s name was Rogelio Muñoz. He was only 53 years old. He didn’t drink, he didn’t smoke, and he was a loyal Tyson worker since 1993. Thank you.”

(In response to a BBC inquiry about Christian Muñoz’s testimony, a Tyson spokeswoman wrote, “We are saddened by the loss of any Tyson team member and sympathize with the family at this difficult time.”)

Four days in the session remained.

The final day of the Nebraska legislature’s 106th session started out with a bit of the feeling of a college graduation. Senators who were leaving office due to term limits stood at the dais waxing nostalgic about their first day on the job, their foibles and triumphs.

Senator Vargas listened from his seat with a vague feeling of trepidation. Several outgoing senators he regarded as political allies and he wondered who would be replacing them. But his thoughts also wandered to what had occurred in the chamber two days prior.

Three days of session passed before the Business and Labor Committee took a vote on his meatpacking amendment. It passed – four yay votes to two nay. But because of the calendar, it was essentially dead on arrival. To move forward to an actual vote would have required three debates, and only two days of the session remained.

On the day it passed out of committee, Vargas spoke one last time about the bill. He reminded the lawmakers that while his time had run out, the governor of Nebraska and the state’s Department of Labor had the power to act at any time.

“I don’t know what else I can do,” he said. “I’m imploring those that can do something, to act urgently to act with compassion and to act with humanity.”

Then he withdrew the amendment and the effort officially died.

Sitting in his office on the final day of the session, an untouched lunch in front of him, Vargas wondered if he had been too naive, wasted too much time believing that a campaign of public pressure would be enough to move the governor or his senate colleagues. He wondered what would have happened if he had gotten those two votes on the motion to suspend – could he have squeaked the bill through?

Still, he was proud to have held a hearing, the first of its kind in the country, where worker testimony was heard.

“Their words are on the record and senators can’t hide from it,” he said. “We have workers testifying. We also have plants not testifying. And we have a committee of elected senators, that majority voted and said, ‘This deserved debate.’ So when I bring this next year, it’s going to get its time again.”

Next year meant January, four months in which health experts warned of a potential second wave. Four months in which the 2020 election would dominate headlines, and the plight of the meatpacking workers would likely fall further and further from the minds of the public. The session, he admitted, had been hard. It had changed him. Before he had faith that if it was a matter of life and death, if he had data and stories, including his own, that he could win the support of his ideological opponents. But he’d experienced something uglier that summer.

“I am the only Latino… it’s inherently a lonely place,” he said. “It is hard bearing that and being vulnerable in front of my colleagues about that. Because it is something that we don’t share.”

Back out on the floor, where the only real business was final reading and passage of bills, a senator named Steve Erdman, from a rural district on the opposite side of the state, rose to speak. He began railing against masks. He espoused the effectiveness of the unproven hydroxychloroquine treatment championed by Donald Trump. He cast doubt on there ever being a vaccine, saying herd immunity was the only way to beat the virus.

“Take your masks off. Go out and live your life because what’s happened here is we’re so afraid of dying we have forgotten how to live,” he said. “If you have the illusion that that mask is going to screen something out and save you, you are wrong.”

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Then a senator, a Democrat named Justin Wayne, took the mic. “I can’t let that go unchecked,” he said. “When people on this floor’s family members have passed. When individuals who are on this floor may have contracted it… I don’t want anybody watching to say that’s not important.” Another Democrat also used his time to chastise Erdman. Yet a third Democrat opined that some didn’t care about Covid deaths because “it wasn’t the right people”. An audibly angry Vargas took the mic, too.

“If you still think this is a joke, please come and talk to me,” he said “I am more than happy to talk to you about exactly every single minute that I was waiting to get a call from the doctor on whether or not my dad was going to get better. And when his CO2 levels dropped or when his lung collapsed – I am more than happy to tell you if that’s going to help you get to a place where you actually understand and take this seriously.”

And then Senator Mike Moser stepped to his microphone. He paused. “I’m having trouble getting my breath, sorry about that,” he said. Moser, a Republican, contracted coronavirus in May and spent five weeks in the hospital. In interviews with the local news, he admitted that he had not been wearing a mask prior to falling ill, and that he’d gone shopping and eaten indoors.

“To take something that you saw on the internet that happens to agree with your contrary personality or your politics and then to represent that as fact, when you don’t know whether it’s fact or not, is irresponsible,” he said. ” You need to… “

His voice broke off, and the sound of his laboured breath through his face mask was audible over the speakers. “You need to have lived through it to understand the helplessness that you feel. There were times I couldn’t even roll over in bed. They had to come in and flip you over, you know? How low are you at that point?” he said, choking up. “Having lived through this, I can tell you this is nothing to mess with.”

Then he told the body that, when laying in his hospital bed one day, his breathing became so strained that he asked a nurse to see if something was obstructing his nasal canal. The nurse took a forceps and removed a blood clot “the size of a little smoky sausage”.

“So you go jam a little smoky sausage up your nose and see how you breathe, and then complain about wearing a mask,” Moser concluded, his voices rising. “Come on, you guys.”

The chamber erupted in applause.

Hours later, after the final gavel had fallen, after the Governor had come to the dais to praise the legislators for passing an abortion method ban and a property tax relief bill, Vargas arrived downstairs in his office. The remarks made by Senator Erdman had obviously angered him. But something else had happened too – as Erdman spoke, Vargas’ phone had lit up with messages of support and concern from the other senators, from all sides of the political spectrum, asking if he was alright and apologising that he had to listen to it. (Senator Erdman did not respond to multiple messages from the BBC.)

He was particularly gratified to hear from Senator Moser, who’d never spoken in such graphic detail about his fight with the virus before.

“He was angry with what Erdman said,” said Vargas. “He’s friends with him, from his own party and he’s just like, ‘People that haven’t been personally affected by this, it’s so easy for them to then just disassociate from it.'”

It was a nice show of support but wasn’t what Vargas wanted – it wasn’t votes, it wasn’t action on behalf of his community.

“One-hundred and fifty-thousand lives have been lost to this because there’s still people who believe that this is a level of collateral damage that is okay. And unfortunately it takes, from some of these individuals, their own loved one to get hurt, or to fall ill or to die. And it should never be that way. You know?” he said. “Anyway, that’s just been like one of the hardest reflections from today.”

Then he went into his office and sent his legislative aide home. For the next several hours, he sat alone. He ate his cold lunch. He slowly packed up his things and sealed the office. It was well after dark when he finally walked down the marble hallways and out the door, the last person to leave the shining state capitol building.

And with that, the 106th session of the Nebraska legislature – for Senator Vargas – came to a close.

Postscript: In the weeks after the end of session, representatives from both the Crete Smithfield and the Lincoln Premium Poultry plants invited Senator Vargas to tour their facilities. He plans to lead a group of fellow senators there later this year. Meanwhile, Nebraska’s governor has moved to reopen most of the state, easing nearly all Covid-19 restrictions.